Sister Margaret Zacharias – Discovering the Diamonds of Poverty

Sister Margaret Zacharias – Discovering the Diamonds of Poverty

Sister Margaret Zacharias

Diamonds Found in Poverty

Imagine the Sylvania Franciscan charism expressed in music. Each simple gesture of love and reverence St. Francis espoused is a musical note that combines with others and becomes a melody. Soon, the song develops into breathtakingly beautiful choral complexities that cannot fail but to reach God’s ears.

Slowly, you become aware of a different note coming from the fifth row, second from the end. The musician is following the choral ‘charism.’ Really, her sound is nearly pitch-perfect. But, it’s unmistakable, you detect a definite vibrational twang.

Well, now, that would be Sister Marge.

In a black-tie orchestra, she’s the one sitting with a harmonica on the porch stoop outside the Concert Hall playing to the homeless guy while he eats her lunch.

Sister Marge is Franciscan in mind, heart and soul. She has two master’s degrees, six belts in Tae Kwon Do and she spent nearly a decade living, in the spirit of St. Francis, among the poor in Brazil and then Africa.

In her years of ministry transition, she’s working part-time as a receptionist in her acupuncturist’s office. Before this, her ministry was as a security guard at Greenfield Village.

“My family always wanted me to be a nice little traditional nun,” Sister Marge recalls with a fond sigh.

God, it seems, had other plans.

_______________

Sister Marge was the 13th child out of 14 and was born in Detroit, Michigan. When she was 16 she entered St. Clare Academy. She took her first vows in 1962, the same year Chubby Checker’s single “The Twist” became a sensation.

Sister Marge began her ministry as a teacher that same year. She taught at Regina Coeli in Toledo, St. Ann in Cincinnati, St. Joe’s in Sylvania and lastly Sts. Peter & Paul School in Detroit and she “enjoyed teaching very much.”

Times, they were a changin’. It was the late 1960’s and post-Vatican II. Aretha Franklin was singing about “Respect” and the Beatles let us know that “All You Need is Love.”

Religious communities, too, were changing. There was a new way of thinking that religious brothers and sisters, despite their rank, should leave the protection of their safe havens and learn to ‘Walk with the People.’

In the spirit of the times, while Sister Marge was at Sts. Peter & Paul, the Sylvania Franciscan Leadership Council asked her to begin a five-year summer Religious Studies program in Cleveland.

At the time, she was only the second Sister asked to pursue Religious Studies. While at St. Peter and Paul, the Diocese invited her participate in the North South American Dialogue Panel where economic models of each were evaluated with emphasis on the role religion plays. She was invited to attend Socialist meetings where she learned various models of socialism and communism contrasted with capitalism.

It was from her participation in the North South American Dialogue that her first big trip evolved. She was given the opportunity to visit Recife, Brazil and partner with Bishop Schoenherr from the Detroit Diocese for a month-long project. In Recife, the diocese was run by Archbishop Dom Helder Camara, who Sister Marge describes as “a living Saint” for his practices in caring for the poor.

“Archbishop Dom Helder turned the Bishop Palace into a place for the poor,” Sister Marge remembers. “He offered a noon lunch for anyone who wanted to eat with him and talk.” This lunch included beggars, missionaries and the town wealthy. Everyone would say their piece and at the end of a half hour, the Archbishop would stand up and say “Help each other.”

The Detroit missionaries’ work was to be among the people, to live as they did and to do what they could to help for one month. They lived in thatched huts. Water had to be carried daily. They ate as the people of the village ate.

This, it turned out, suited Sister Marge immensely. “As a novice I chose ‘poverty’ as my main interest,” she admits.

In Brazil she was able to understand the complexity of poverty. “Poverty became a diamond in my mind, because there are so many facets to it,” she says.

Sister Marge explains it this way: In the beginning poverty is mainly physical. You must get accustomed to not having what you need, lacking food, comfort and cleanliness. Next you begin to detach yourself from being hurt inwardly by scorn. As you begin letting go on both levels you begin to achieve a detachment and “interior freedom.”

“We learned to look at life from the bottom up. We learned not to judge and to simply help people to find a way to make taking the next step a little bit easier,” Sister Marge says.

“We walked with the people. As we spent our days and evenings with them, we raised their consciousness of their worth by teaching the scripture that they are the image of God. When they were able to understand that, they would begin to understand that they deserved to live better and that they could live better. This dignity empowered them.”

“It was wonderful. I loved Brazil and the people immediately. That trip was a life-changing moment, but at that point it was just a moment in my life.”

When Sister Marge finished her studies she was assigned to be the Religious Education Coordinator at St. Ann’s in Cincinnati, where she remained for over three years. This would be her last conventional position for some time.

_______________

In 1977, Sister Patrice, Congressional Minister at the time, asked Sister Marge a surprising question.

“What would you like to do?”

Sister Marge took some time to consider her answer.

She felt drawn like a magnet to Brazil, the people and the ministry she’d experienced. She consulted with Bishop Schoenherr the director and secured a place with his team.

Finally, proposal in hand, Sister Marge gave her answer. “I think I’d like to go back to Brazil.”

Leadership Council approved and a few weeks later she landed in her new home and her new ministry in a barrio in Recife.

As the months passed, she found herself increasingly drawn to work with the street dwellers in the city. There she joined ranks with Fr. Larry, an oblate from a different mission, who had been living among the homeless for some time.

She decided that she wanted to adopt the street dwellers as her full-time mission. Fortunately, she received approval from Dom Helder and also the Oblates who supported the ministry, which garnered her the support from the Leadership Council and the Detroit Diocese.

“I lived on the streets with the people,” Sister Marge says happily. She slept on cardboard with the other homeless people and they ate a daily meal together, which was soup made from scraps gathered in the marketplace after it closed for the day. She stood with the women and children when the police came to arrest everyone. She went to jail with them, using her status to keep them safe and calling on Fr. Larry to use the influence of Archbishop Dom Helder Camara to get them all out.

When Fr. Larry went to jail with the men, she would work to get their prompt release as well.

As closely as possible, Sister Marge lived with the people as St. Francis might have done. Still, she had an Achilles’s heel.

“I couldn’t get used to not bathing. I could only go about three days,” she admits.

She found a sympathetic bath available to her at the nearby Benedictine Cloister. Sometimes, when the police had sent all of the street people into hiding, she’d take refuge in the Cloister and sleep on a cot for the night.

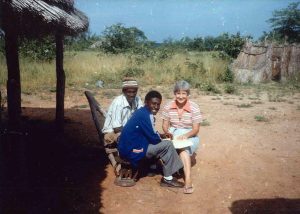

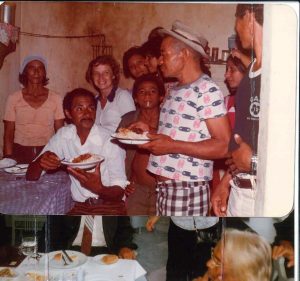

In her photographs she looks very happy. In one photograph, Sister Marge, young, pretty and petite, is laughing as she stands amid a group of the people she lived among. They wear mismatched ill-fitting clothing. Their poverty is unmistakable.

Sister Marge, third one in from the left, watches the man in the hat with glee; she can tell he is about to do something very funny.

“So, too, is their joy,” says Sister Marge. “They knew how to have such a good time.”

When the marketplace quieted and emptied for the evening, they would come together in the vacant stillness and light a fire to make soup, each contributing to the meal what they could, typically vegetables collected from fallen carts throughout the day. While it cooked, they would tell each other the stories of their day. The young boys would have spent the day selling ‘cafezinhos,’ which were little cups of sweet black coffee. Some would have spent the day in a long line, trying to get documentation, medical care or other services. Still others would have been selling cardboard or bounty found in the trash. They would sing and pray and say the Our Father. And then they would eat.

“There was no concept of greed or gluttony,” Sister Marge says.

She remembers being particularly struck by this when she heard somebody ask a man if he would like a bowl of soup. He replied with great simplicity: “No, I’ve had my bowl today.”

When the food was cleared away, everyone would gather near the fire. Soon one of the men would bring out a stick or a hat and the prop would become part of a character he would begin to play.

“The people were great mimics,” Sister Marge relates. “They would pick someone around the fire or someone we all knew and do an outstanding improvisational portrayal. They thought it was hilarious to mimic me,” she smiles.

After their fire they would recede into the shadows and find places to sleep, sometimes in larger groups and sometimes singly, depending upon where they felt safe and where the police was rumored to be that night.

Although it was a very hard life, she found it “so liberating to live like that.”

“What I was practicing made sense and it resonated with what I believed in – living honestly. What do you need in life? Nothing really,” Sister Marge adds.

_______________

A few years later, she returned to her hometown in Hamtramck, MI, to be with her sister who was dying. While back in the area, she also organized a Justice and Peace Center for the Sylvania Franciscan community that brought six Christian denominations, some Jewish and Muslims members, and six human rights organizations together. In one initiative, they hosted ten Russians and brought them together with the Sylvania community to give everyone a chance to start a conversation without the political hype that dominated the environment at the time.

This exchange led to members of the Justice and Peace Center travelling to Russia for a two-week stay. During the day they engaged in peacemaking dialogues talking to Russian Catholics and clergy in the Russian Orthodox Church about the challenges of being religious in a secular communist state. For Sister Marge, the trip included a delightful trip to see the Russian Ballet Company perform.

While working with the Justice and Peace Center, Sr. Marge was also working with Bishop Hoffman of the Toledo Diocese who was deeply interested in the concept of adopting a site and bringing their mission to them. With her experience in Brazil, Sister Marge was a natural to tap as the project researcher and eventually to be a missionary for the expedition.

After close study, she recommended Zimbabwe because the war had recently ended and there seemed to be a general openness to missionary involvement.

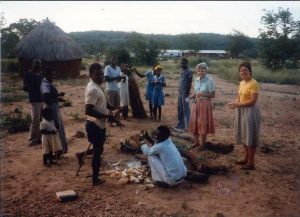

The project’s ethos was “Mission of Accompaniment,” which meant that their goal was to work with the people to adopt helpful techniques for building their community. The Diocese intended to invest ten years, then transition the mission to local lay people under the guidance of the Hwang dioceses in Africa.

“We began with the understanding that everything we did was with the people and would be turned over to the people.”

Zimbabwe had a polygamous social structure. One man married several wives and the children were raised by all of their ‘mothers.’ These units were known as ‘kraals,’ and several kraals comprised a village and each village had a Chief. When Zimbabwe became independent the chiefs lost their power. The idea was to empower the Chiefs to better identify needs and formulate solutions for their own villages. The mission itself put up most of the money needed but required the villagers to participate fully.

“For example, the village women said that they would like a sewing machine, which cost about $40. We told them that if they could raise $5, we would pay for the rest,” Sister Marge says.

Zimbabwe had become quite the tourist attraction before the war, so with whatever spare time they had, the women worked on making baskets to sell to the travelers and the men made carvings from local wood. In time, they had saved up the money.

Another time, the women asked for more water holes. The chiefs were invited to select one person from their village to go learn the craft of digging wells, with the tuition financed by the Mission. When the newly trained person returned, the Chief had the responsibility of ensuring that the new water holes were developed for their village.

Throughout the years they also helped send students from each village off to secondary school. They read lots of scripture with the villagers. And they ate eggplant.

“We ate eggplant nearly every day. Meat was not easy to come by and so eggplant played a large role in our diet,” Sister Marge explains.

(She has never eaten eggplant since.)

After working to develop the Zimbabwe project for a few years, Sister Marge decided it was time to return to the states. She took a short pause to debrief and accustom herself to life in America. She then found a place to use the skills she’d acquired.

The United States Catholic Mission Association in Washington, D.C. needed an Assistant. Her Councilor Sister Ruth Marie encouraged her to take the job and Sister Marge went to D.C.

She spent five years in D.C. helping the Director work with clergy heading off to missions as well as handling their debriefing upon return, organizing conventions and a host of communications designed for both the diocese and missionaries. As the Assistant to the Director, Sister Marge was also asked to serve on dozens of committees over the years.

(Busy as she was, it was here that she found time to pick up six belts in Tae Kwon Do.)

Her position at United States Catholic Mission Association also served as a springboard for even more trips abroad.

“Most of the places I’ve traveled was because they needed a Sister,” Sister Marge laughs.

The International Fellowship of Peace Reconciliation wanted to meet with Saddam Hussein in order to make a statement of peace and show support for breaking the embargo. They needed a nun who had a passion for human rights, so they called Sister Marge.

Thinking back, she realizes, their idealism makes them sound like hippies.

“The 80’s were a great time to be active. It felt like everyone was reaching out to make the world a better place,” she explains.

For the trip, Sister Marge organized with the Sister of St. Francis of Sylvania sponsored hospitals, Holy Cross and Providence who donated several big boxes of medical equipment to Iraq.

Sister Marge and Muhammad Ali happened to be part of the same envoy to Iraq; she recalls him entertaining the rest of the group on the trip over.

While on the mission, she met both Muhammad Ali and a delegation of Lakota Sioux who were also involved with the peace talks with Iraqis. While on the boat to Bagdad, Muhammad performed magic tricks to help keep everyone calm. She smiles, remembering the Sioux sitting outside the Embassy every afternoon hoping that Saddam Hussein would come outside and smoke the peace pipe with them.

Sister Marge spent her afternoons with an interpreter meeting with farmers, students and villagers who lived there; she was always interested in the role of the church and was granted an audience with the Chaldean Archbishop.

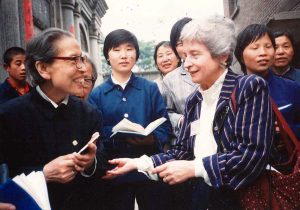

Sister Marge on a trip to facilitate dialogue between the Roman Catholics under the Pope living in Beijing and the Patriotic Church, under the Chinese Government.

In 1989, a group heading to China needed Sister Marge to step in for a Sister who became ill right before the trip. She traveled with a group of approximately 20 clergy to Beijing to help coordinate the logistics of the trip.

Their mission was to facilitate dialogue between the Roman Catholics under the Pope living in Beijing and the Patriotic Church, under the Chinese Government. Unfortunately, the visit was cut short after a week. She received an urgent call from their guide that they must leave; he’d scheduled them to board a plane and leave the country immediately. They left Beijing at midnight on June 3; the massacre in Tiananmen Square began the next day.

“When I saw what had happened I literally couldn’t speak for weeks. I had a psychosomatic reaction to those kids being mowed down and I personalized the fact that they had been silenced by not having any voice left myself.”

The ties of family began to pull at Sister Marge in the early 1990’s when siblings and cousins began to suffer health issues. In 1992 she accepted a position as a Pastoral Associate at Christ the Good Shepherd parish in Lincoln Park, MI, where she could be near home.

“The timing was right. Not only was I was needed at home, but I was ready to return to a parish,” Sister Marge says, noting that she stayed at the parish longer than she had stayed anywhere else.

In the end she stayed twelve years. After the pastor of the parish was transferred, she decided it was a good time for her to change gears once again.

A two-week visit to Israel during those years had left her wanting to go back. She requested a sabbatical. While waiting for her paperwork to stay in Israel, she spent a year as a foster caregiver at El Ranchito de los Ninos in Los Lunas, NM before moving to Israel and attending the Tantur Institute in Jerusalem.

“I’d become fascinated with the Middle East and something of an expert on relations there. I’d always wanted to go to Israel and with Leadership’s blessing, I was able to go.

As a friend of mine remarked, I went to Israel an Israelite and returned home a Palestinian,” says Sister Marge, who remains to this day a vocal supporter for Palestinian rights.

Within a span of three years, Sister Marge helped bury five sisters, one brother, two sisters-in-law and a niece.

“I was glad to be able to be home to help and have the time to be there for my family,” Sister Marge says.

After returning from the Mid-East, she presented the Leadership Council with an unusual mission request. She wanted to continue to contribute but didn’t feel that the scale of her family’s personal needs would permit her time for a mainstream ministry. The convenience of the Henry Ford Museum intrigued her and she gave it a closer look to see if there was anything she could do there.

“The more I thought about it, working as a Security Officer was not only something I was suited for, but it really was an important ministry.”

She presented a compelling argument to Leadership that the role of security guard is really a secular but very Franciscan ministry in that the goal is to serve, educate and help with either first aid, hospital runs and lost children.

Once again, they agreed.

Sister Marge thought that it would be ideal for a year or two, giving her the chance to continue to care for her family. Instead, she remained there for over a decade and only gave that up when a recent accident left her with her own physical rehab and pain management to handle.

Sister Marge is treating her pain as one might expect – by using both western and eastern medical practices and a whole lot of prayer and meditation.

“Ring the bells that still can ring. Forget your perfect offering. There is a crack, a crack in everything. That's how the light gets in.” --- Leonard Cohen

Sister Marge careens around cheerfully in front of her family home in Hamtramck while on a two-week visit.

Sister Margaret Zacharias was born at a time when the country was poised to shift direction and women religious were taking a front row seat to this change. Sisters of St. Francis of Sylvania were at the front lines when Polish immigrant children needed schools, when war and disease shook families to their core and when other communities worldwide needed them.

Sister Marge’s ministries led her throughout her life to seek to understand poverty by being present, listening, and teaching that every single one of us are created in God’s image.

“The opportunities that presented themselves to me were unique. My life has been a natural thing that unfolded,” Sister Marge says simply.

Sister Marge asks, “When you’re dying, what do you want the last word on your lips to be?”

Hers? Gratitude.

If you would like to send a message to Sister Marge, email Elizabeth Reiter at ereiter@sistersosf.org

By Elizabeth Reiter