Saving Grace

February 6, 2015

My Lenten Signature

February 20, 2015By Sister Nancy Linenkugel, OSF

Cincinnati’s Observatory is the oldest professional observatory in the United States. Originally a key facility for astronomical research dating back to 1843, today the Cincinnati Observatory remains part of the University of Cincinnati and is devoted to education. The facility actually has two observatory “domes”—one for the 11” oldest refracting telescope in the world and the other for the “newer” 1904 16” refracting telescope. The Cincinnati Observatory operates as a 19th century observatory with all manually-controlled levers and cranks to rotate the domes, to open the slit, and to position the telescopes via non-computerized latitude and longitude.

Taking part in an astronomy program on a cold but clear 18° evening is the first indication that I’m a neophyte when it comes to observatories. What was I thinking? Of course the domed slit would be open so that the telescope can capture the sky, and of course that means that the air temperature around the telescope inside the domed room would be the same as outdoors—cold! No, make that, very cold.

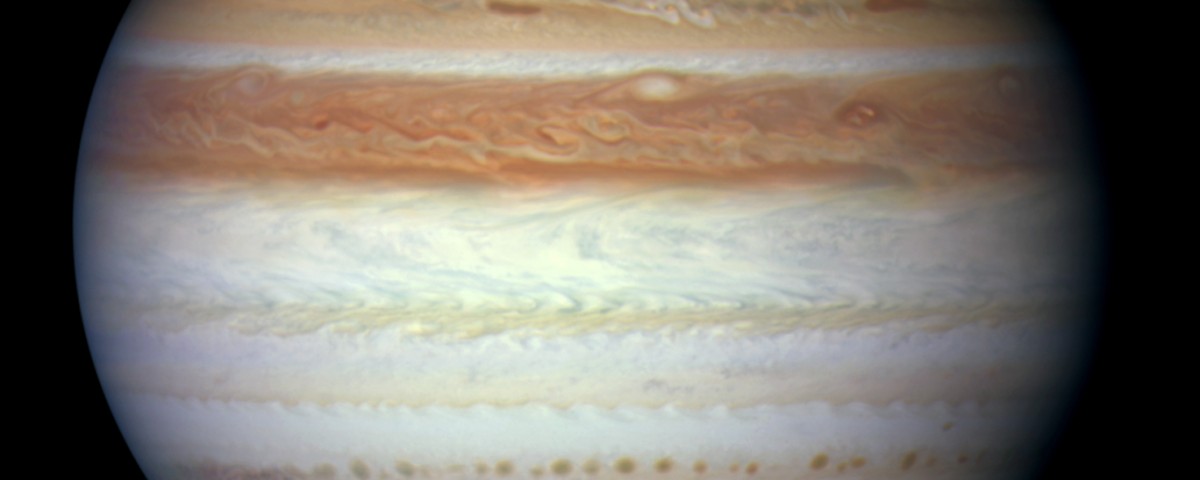

It was a winter sky so Jupiter was easily in the scope as was the constellation of Orion. From growing up around the Lourdes University planetarium, even I could identify the three stars comprising Orion’s belt.

There were about 20 of us taking part in the evening’s program, and we inched our way around the circular wall as we each ascended the rolling staircase to take our individual turns looking through the telescope. A steady stream of “oohs” and “wows” arose from each person at the eyepiece once our human eyes finally focused on what the observatory staff intended for us to see—Jupiter’s stripes, Jupiter’s moons, the nebulae, and then the stars in Orion after the telescope was repositioned.

In the “Laudes Creaturarum” or the “Canticle of the Creatures” we pray St. Francis’ well-known words: “…Praised be you, my Lord, through Sister Moon and the stars, in heaven you formed them clear and precious and beautiful.”

Francis didn’t use a refracting telescope to look at the stars when he composed that prayer. He didn’t even use his own eyes, since by 1225 when he composed the prayer he was blind from eye ailments. No, he composed that beautiful Canticle simply from the eyes of his memory and from his deep belief in creation’s unity with God.

And so almost 800 years later, I join St. Francis in thinking about the beauty of the night sky in its changelessness and with its “clear and precious and beautiful” stars. Francis saw those same heavenly bodies that I was looking at. And then he did something about it—he composed an enduring prayer. I made myself stop shivering from the cold long enough to pray his enduring prayer.